Reliability and steadiness are essential to any successful career, whether you’re a teacher, a doctor, an engineer, or a barber. That’s because these qualities are directly tied to long-term performance.

You won’t achieve success over the years if you don’t stick to your principles, if you fail to learn from your mistakes, or if you regularly change your approach without good reason. We know this to be the case in our working lives, but when it comes to investing, studies show that a majority of individual investors do just the opposite: They unreliably change course all the time, and not surprisingly, the results are dismal.

Missing most of the upside

The best-performing mutual fund from 2000 to 2010 was the CGM Focus Fund (CGMFX), which returned more than 18% annualized despite a flat S&P 500. The fund’s outstanding track record would have turned $100,000 into more than $500,000 over those 10 years. The only problem? According to Morningstar, the average investor in the fund actually lost 11% annually over those same very successful 10 years. That is not a typo: The fund gained 18% annualized, but its average investor lost 11% annualized. You’re not crazy to ask how that is possible.

The answer is that many fundholders tried to time the market. For example, the fund soared 80% in 2007, so hordes of investors poured money into it in 2008 — only to see it fall 48% that year. That decline led investors to pull money out in 2009, taking losses soon before the market soared from its low. Investors were making emotional decisions based on recent events, changing their stance repeatedly, and as emotion would have it, at the most inopportune times.

Not just one fund; it’s universal

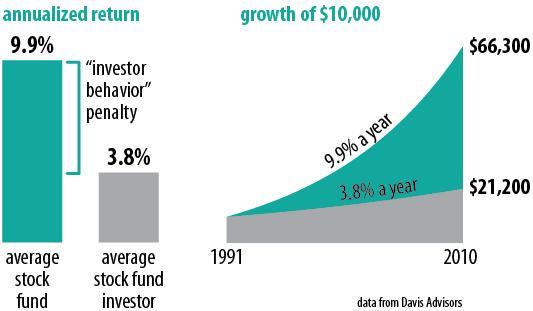

According to an investing study from Davis Advisors, the average stock-holding mutual fund returned 9.9% annualized from 1991 to 2010, but the average fund owner earned only 3.8% on average per year.

Not pretty. And it hurts even more if we put this performance into dollars. By trading in and out of funds, the average fund owner increased a $10,000 investment to just $21,200 over nearly two decades — while the average fund turned that $10,000 into $66,300. Now imagine the continuing effects of compound returns on both of those amounts and the growing difference between them over a lifetime. Feel the pain. Remember it next time you’re tempted to make a trade. Davis also finds that the less trading a fund itself does, the better the fund’s results tend to be. What’s true for individuals is true for funds, too.

Successful investing includes many bad years

All great investors suffer years of poor results, bar none. It’s just how the market is. Warren Buffett’s partner, Charlie Munger, has an outstanding lifelong record, but his annual results lagged the S&P 500 index 29% of the time. An impatient investor would have left Munger during some of his down years and missed out on riches later.

And Munger is far from alone. According to Davis Advisors, investors who achieve the strongest records aren’t always at the top of the performance list. Over a 10-year period, Davis studied 192 large-cap money managers who had previously ranked in the top 25% for performance. They found that:

- A full 93% of them spent at least one three-year period in the bottom half of all performers.

- Sixty-two percent of them spent at least one three-year period among the lowest 25% of all performers.

- And 31% of the best money managers spent at least three of 10 years among the very worst 10% of all performers!

In other words, over this 10-year period, you could expect most of the best investors to be ranked among the very worst about one-third of the time.

This data clearly illustrates why impatient investors lose out: They go from vehicle to vehicle seeking results based on recent performance. They sell when one asset is down only to buy another asset that may be up recently, but that asset is just as likely to go down next — because nearly all investments and all investors have weak periods. As we showed above, chasing performance by looking in the rearview mirror can turn a 9.9% annualized return into 3.8%. Sitting tight would be so much better.

Stay the course

As with any career, steadiness and persistence are necessary for successful investing. But don’t take that to mean you’ll always do well. There will be years in which your results disappoint you, and years in which your successes are far greater than you thought possible. That’s why it’s vital to invest in ways that truly make you comfortable, so you don’t lose faith during rocky periods. Because the final point to remember is that historically, 10-year periods of weak stock market performance are followed by 10 years of much stronger results.

—

Written By Jeff Fischer, The Motley Fool

Reproduced here with permission